Fly with care: avoiding disturbance when using drones to study cetaceans

A new study outlines recommendations to minimize the potential for negative impacts when using drones to study beluga whales and other cetaceans.

Drones have been widely used in the last decade for a host of wildlife studies. They’ve been particularly helpful to advance our understanding of whales, dolphins, and porpoises, because cetaceans are notoriously difficult to observe in their natural environment. But can drones disturb the animals that we strive to understand?

Our study “Fly with care”, published in Marine Mammal Science, investigated that important question. We analyzed 143 drone flights obtained with a DJI Phantom 4 and Phantom 4 Pro (both used extensively in drone wildlife studies) over 27 days, for 28 beluga herd encounters. The footage had been originally collected to study various aspects of beluga behaviour and ecology. We looked at drone altitude, speed, and approach angle, in addition to group size, composition, and behaviour, and evaluated the reaction of the whales based on a series of defined alert and evasive behaviours.

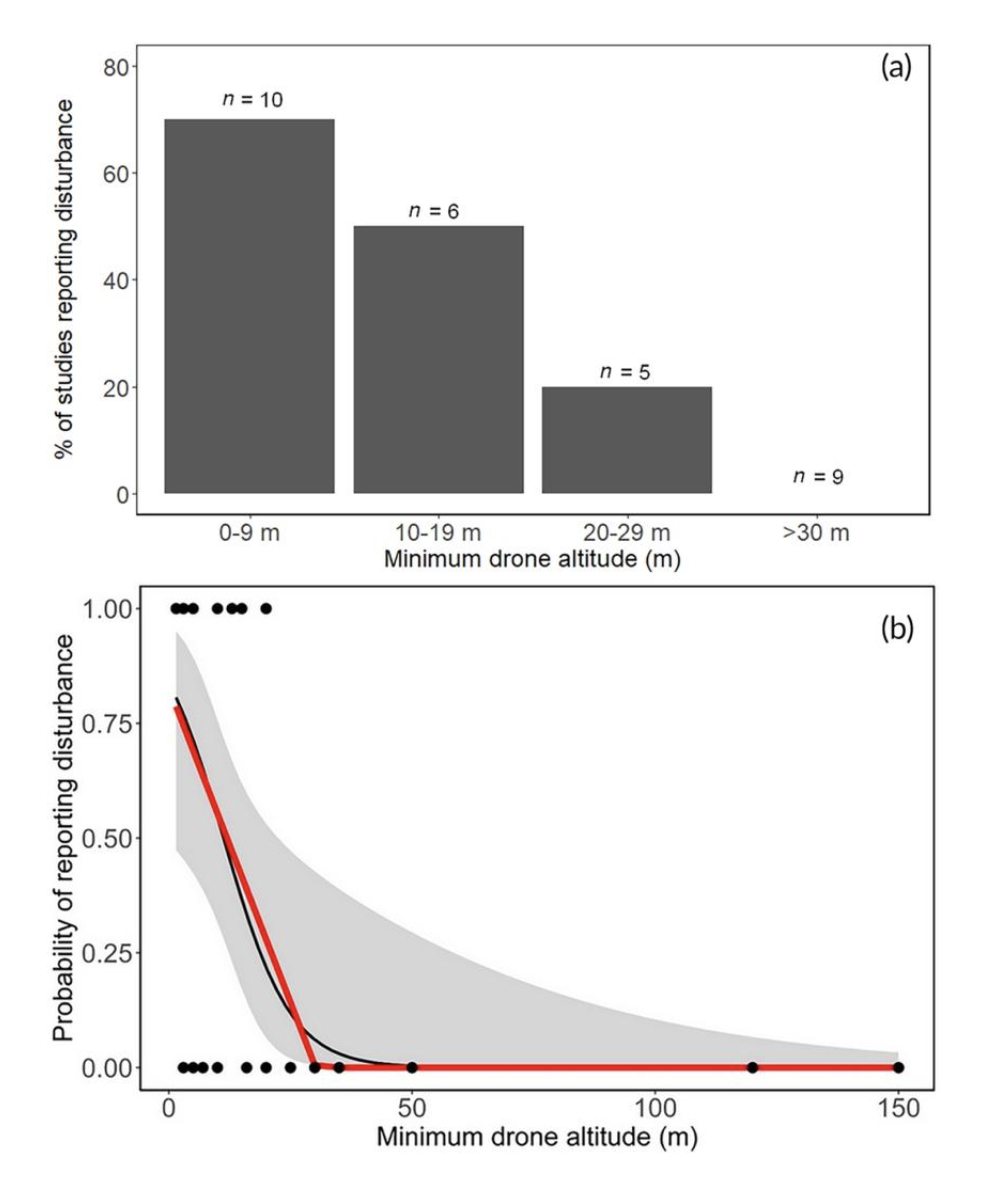

We also conducted a systematic literature review to examine the impact of drone altitude on cetaceans. Of 72 drone studies of cetaceans published from 1979 to 2022, only 31 studies reported drone disturbance and altitude thresholds. We compared the results of such studies with our own.

Based on both the results of our video analysis, and on our review of the literature on cetacean drone disturbance, our paper lists recommendations that apply the precautionary principle and encourage researchers to minimize the potential for negative impacts when using drones to study cetaceans. The main recommendations are that drone-assisted studies of belugas that involve small drones maintain a lower altitude limit of 25 metres, a threshold below which evasive responses were more likely, both in our study and in the literature, and that large groups should be approached with special caution due to the increased likelihood of reactions.

Please follow local regulations when flying drones recreationally

Under the Canadian federal Marine Mammal Regulations, it is illegal to approach marine mammals with an aerial drone at an altitude below 1000 feet (about 304 metres) within a half nautical mile (about 926 metres). Flight maneuvers, including taking off, landing or altering course or altitude, are also not allowed near them.

Ethicals

Our fieldwork methods were reviewed and approved by the Memorial University Animal Care Committee (Animal Use Protocol: 20190640). Our research, and specifically, the use of research drones in the Saguenay St. Lawrence Marine Park was covered by research permit SAGMP-2018-28703 issued by Parks Canada and QUE-LEP-001-2018 issued by Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Citation

Aubin, J. A., Mikus, M.-A., Michaud, R., Mennill, D., & Vergara, V. (2023). Fly with care: belugas show evasive responses to low altitude drone flights. Marine Mammal Science, 1– 22. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12997

Abstract

Drones have become an important research tool for studies of cetaceans, providing valuable insights into their ecology and behavior. However, drones are also recognized as a potential source of disturbance to cetaceans, particularly when flown at low altitudes. In this study, we examined the impact of drones on endangered St. Lawrence belugas (Delphinapterus leucas), and reviewed drone studies of cetaceans to identify altitude thresholds linked to disturbance. We repurposed drone footage of free-living belugas taken at various altitudes, speeds, and angles-of-approach, and noted the animals’ reactions. Evasive reactions to the drone occurred during 4.3% (22/511) of focal group follows. Belugas were more likely to display sudden dives during low-altitude flights, particularly flights below 23 m. Sudden dives were also more likely to occur in larger groups and were especially common when a drone first approached a group. We recommend that researchers maintain a lower altitude limit of 25 m in drone-assisted studies of belugas and approach larger groups with caution. This recommendation is in line with our literature review, which indicates that drone flights above 30 m are unlikely to provoke disturbance among cetaceans.

Select figures

Authors and affiliations

Jaclyn A. Aubin and Dan Mennill, Department of Integrative Biology, University of Windsor, ON, Canada

Robert Michaud, Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM), Tadoussac, Québec, Canada

Marie-Ana Mikus and Valeria Vergara, Raincoast Conservation Foundation, Sidney, BC, Canada

You can help

Raincoast’s in-house scientists, collaborating graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and professors make us unique among conservation groups. We work with First Nations, academic institutions, government, and other NGOs to build support and inform decisions that protect aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, and the wildlife that depend on them. We conduct ethically applied, process-oriented, and hypothesis-driven research that has immediate and relevant utility for conservation deliberations and the collective body of scientific knowledge.

We investigate to understand coastal species and processes. We inform by bringing science to decision-makers and communities. We inspire action to protect wildlife and wildlife habitats.