Vanishing goats? Not on the watch of the Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation

New research shows that mountain goats in Kitasoo Xai’xais territory and beyond in British Columbia are of conservation concern.

Wildlife populations can too often decline before wildlife managers notice. Although counting animals is one of the most fundamental activities biologists do, it is also the most difficult. Newly published research by the Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation (KXN), the Raincoast Conservation Foundation, and the University of Victoria shows the importance of listening to those that have lived near wildlife for millennia. Their findings, published in the open-access peer-reviewed journal, Conservation Science and Practice, show that mountain goats in KXN territory and beyond in British Columbia are of conservation concern. First to detect the changes, the KXN will be the first to address them with conservation management.

The first signs happened decades ago. KXN community members began to report a decline in sightings of goats once frequently seen from river valleys and the ocean. These patterns were alarming, given the immense cultural value of goats to the Kitasoo Xai’xais people.

“Historically, access to goats influenced the location of village sites and camps. Alarmingly, we don’t see goats in these locations anymore, a dramatic decline from several decades ago,” said Douglas Neasloss, Chief Councillor of the KXN.

Motivated by these early alarm bells from the community, the KXN compiled multiple independent, but complementary, data sources. First, they conducted comprehensive interviews with knowledge holders who collectively had centuries of knowledge and experience in goat country in Kitasoo Xai’xais territory. Participants were asked how frequently they saw mountain goats from 1980 to the present day. The result was a striking decline in the number of goats observed over this time. In 2019, when the interviews were conducted, no one had even seen a goat that year.

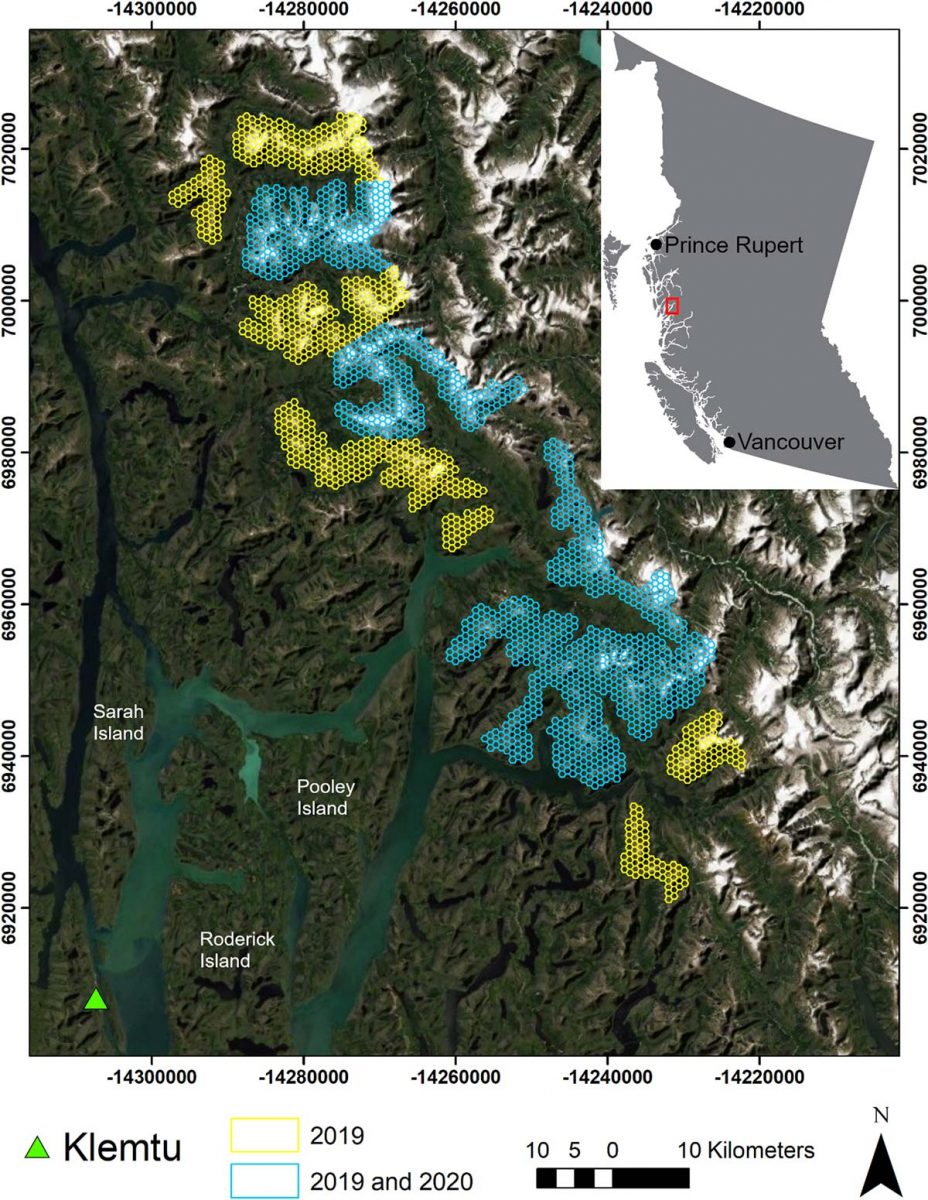

Secondly, the KXN led helicopter surveys across more than 500 km2 of KXN territory in the summers of 2019 and 2020 to better understand contemporary mountain goat density. Building upon their own wildlife research program, the KXN collaborated with a team of wildlife scientists, led by Tyler Jessen, PhD student at UVic and scholar with the Raincoast Conservation Foundation, to analyze the data. Results show that KX goats occur in low density, especially when compared to interior populations, such as those that inhabit the Rocky Mountains.

Finally, wanting broader context and yet another independent source of information, the research team also examined hunting records that stretched across BC and back to 1980. They found that the success of BC hunters (unaccompanied by professional guides) has declined over the past four decades. All else being equal, if a hunter has to spend more days looking for a goat to kill than they did in the past, then there may be less goats than there were before. This pattern occurs well beyond KXN territory.

Collectively, these information sources all pointed to the same reality: that mountain goats are of conservation concern in KXN territory; either the abundance or distribution of goats has changed – possibly both. There are either less of these creatures, or they spend more time at high altitudes where they cannot be seen or hunted easily. If they are at higher elevations, this means that something is driving them upwards, such as warming alpine temperatures, which can cause heat stress. Additionally, mountain goat food quality and quality are often reduced at higher elevations. Combined, both of these factors can ultimately lead to population decline.

Either way the Kitasoo Xai’xais, having first detected these patterns, are not going to let these goats slip away. Their thick white coats are adapted to the chilly mountaintops, but as alpine temperatures rise, goats might have less habitat left to escape the heat. Against this climate change background and towards a precautionary approach to reflect the uncertainty around population abundance, the KXN will look to adopting management measures to safeguard these precious and culturally important animals from other harms. Specifically, the KXN are exploring tightening up restrictions within their territory including high-elevation logging, air traffic access, and hunting. Indeed, KXN members voluntarily stopped goat hunting decades ago in response to reduced sightings.

Shedding light on an elusive mountain animal would not have been possible without early insight from KXN. As Jessen explains, “A broader takeaway from this study is that Indigenous peoples commonly detect changes that go undetected by western scientists and managers.”

This study highlights a growing resurgence of Indigenous research and management and shows how pairing Local Ecological Knowledge with scientific information can enhance our collective understanding of ecosystems.

Citation

Jessen, T. D., Service, C. N., Poole, K. G., Burton, A. C., Bateman, A. W., Paquet, P. C., & Darimont, C. T. (2022). Indigenous peoples as sentinels of change in human-wildlife relationships: Conservation status of mountain goats in Kitasoo Xai’xais territory and beyond. Conservation Science and Practice, 4( 4), e12662. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.12662

Abstract

Local people can act as sentinels for change, especially for wildlife populations not monitored by centralized governments. Responding to concern expressed by the Kitasoo Xai’xais (KX) First Nation over a decline in mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus) sightings, our community-academic partnership assessed the conservation status of goats in KX territory and beyond in British Columbia by evaluating three independent information sources. Aerial surveys (2019 and 2020) over 542 km2 revealed a low-density population (mean 0.25, SD 0.12 goats/km2), typical of peripheral coastal range. Interviews with KX Knowledge Holders revealed that sightings from sea level have declined sharply over 40 years, a period during which temperatures have increased and snowpack has decreased. Finally, Kill data (1980–2018) showed that kills/hunter/day initially increased among guided hunters before plateauing, but declined among resident hunters (~70% of hunt days) in both coastal and interior BC. Convergent patterns among datasets suggest that coastal goats declined in abundance and/or reduced use of low-elevation habitat, disrupting a millennia-old relationship between KX people and goats, thereby posing a conservation concern. Broadly, our work shows that detecting threats to peripheral populations, and wildlife in general, can be informed and empowered by the knowledge of place-based peoples and associated decentralized management. Kitasoo Xai’xais First Nation mountain goat research illustrates roles of Indigenous peoples as sentinels of population and ecosystem change.

Select figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Authors and affiliations

- Department of Geography, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

- Raincoast Conservation Foundation, Sidney, British Columbia, Canada

- Stewardship Authority, Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation, Klemtu, British Columbia, Canada

- Aurora Wildlife Research, Nelson, British Columbia, Canada

- Department of Forest Resources Management, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

- Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

You can help

Raincoast’s in-house scientists, collaborating graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and professors make us unique among conservation groups. We work with First Nations, academic institutions, government, and other NGOs to build support and inform decisions that protect aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, and the wildlife that depend on them. We conduct ethically applied, process-oriented, and hypothesis-driven research that has immediate and relevant utility for conservation deliberations and the collective body of scientific knowledge.

We investigate to understand coastal species and processes. We inform by bringing science to decision-makers and communities. We inspire action to protect wildlife and wildlife habitats.