Hatcheries: good intentions, bad outcomes

Our new animation delves into the history of hatcheries and the future we envision for wild salmon.

Walk into a large salmon hatchery and you will find a place not unlike an industrial assembly line. On one side of the facility, adult salmon arrive in giant plastic totes where workers are ready to receive them, clubs in hand. Once dispatched, the salmon are stripped of their eggs and milt. The eggs are fertilized in buckets, then transferred to racks where they sit in flowing water until they hatch. High up on a wall, you might see a scoreboard that displays the day’s figures for curious visitors: 150,000 EGGS TODAY, 2.5 MILLION EGGS TO DATE.

This isn’t a fish farm, but the fish being grown aren’t wild either. Unlike wild salmon, these fish will hatch in plastic trays and grow in contained tanks until they reach a certain size;only then are they released into a river.

Our second video in our new animation series, Ripple Effect, dives into what happened in the 1970s, when the “wild” idea of simply making more salmon was born.

Despite our best intentions, our intervention in the salmon life cycle has had unintended consequences. Adding hatchery salmon into the ocean can bring on an onslaught of problems for wild salmon, including reduced genetic diversity, competition for food, and increasing fishing pressure on wild fish when they migrate alongside hatchery fish.

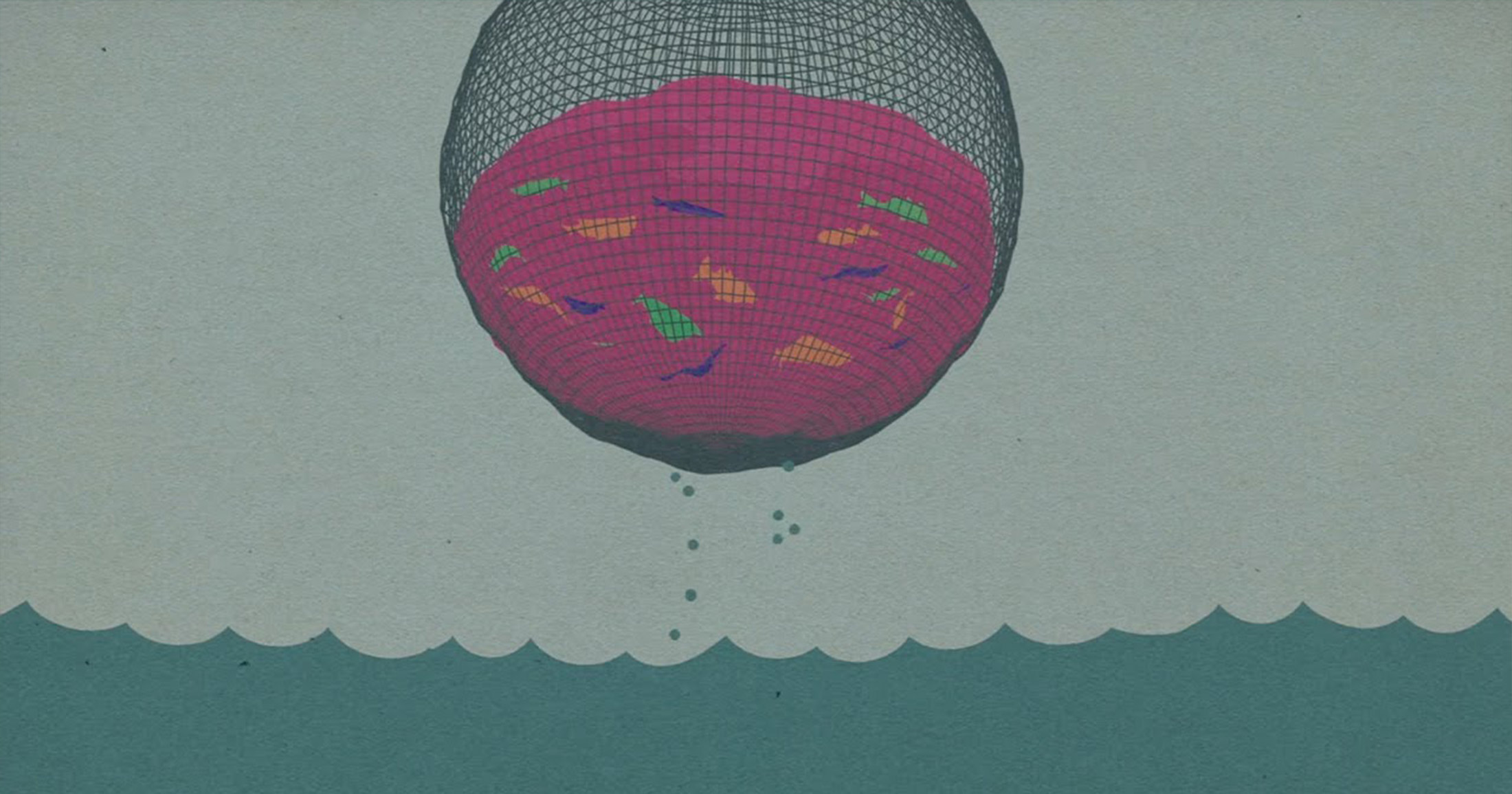

Currently, there are at least 243 salmon hatcheries on the Pacific coast of western North America. Between the five salmon-producing countries in the North Pacific (Russia, Japan, Canada, USA, South Korea), five billion hatchery fish are released into the ocean each year.

It may be odd to think about, but at a time when more wild salmon populations are at risk of extinction than ever, the North Pacific has never been so chock full of salmon. The reason? The number of hatchery fish to wild fish is on the rise, and dramatically so.

What is a hatchery?

Hatcheries are facilities that raise salmon from egg to smolt in tanks, with the intention of releasing the fish into the wild. Potential predators are kept out of the hatchery by concrete walls and barrier nets. A network of pumps, oxygenators, and filtration systems keep the water at near-ideal conditions. Combined, these factors within the hatchery walls result in a higher rate of survival for young salmon (called “egg-to-smolt” survival) compared to eggs and fry growing in the wild rivers.

On the surface this sounds like a great idea. More surviving juveniles should mean more adults returning to spawn. This line of thinking has captured the minds of fisheries managers across North America since the late 1800’s, when the first fish hatchery operations came to life.

In the early 1970’s, as wholesale destruction of salmon habitat for industry was occurring and overfishing ran rampant, hatcheries were seen as a way to prop up a booming commercial fishing industry without having to introduce any constraints on logging and development to protect habitat, or change unsustainable fishing practices.

Now, new research is making us rethink how hatcheries are used and determine whether they are beneficial, or even harmful, to wild salmon recovery.

Hatcheries have adverse effects on wild fish

Fish raised in a concrete facility are different from fish that hatch in a natural stream. Wild salmon have adapted over millennia to be uniquely suited to the rivers which they return to. Over generations, evolutionary pressures such as shifting river conditions, competition for resources, predation, disease, and mutations have shaped the DNA of wild salmon to maximize their genetic fitness in the ecosystems where they live.

Generations of raising fish in hatcheries creates fish that are poorly suited for life in the wild. Evidence shows that once young hatchery salmon are released into the ocean, they have lower survival rates compared to wild fish. In an era of shifting environmental conditions due to climate change and habitat loss, the gene pool of wild fish plays an integral role in building resilient populations.

Further, this pool of DNA has a feature that we are just starting to fully appreciate: epigenetics. Millions of years of changing ocean and freshwater conditions have given wild salmon a cortege of unplayed cards that are stored as unexpressed genes in their DNA. Just as in a card game, where the strategy evolves based on the cards in play, the unused genes represent the potential within the genetic code to be influenced by new conditions that adapt in response to changing environmental cues. This gene pool will be vital to salmon resilience in a hotter and drier world.

When hatchery fish breed with wild fish, they pass on their sub-par genes, diluting the wild gene pool and reducing the overall genetic fitness of the population. Over time, life in the hatchery ‘domesticates’ the wild salmon gene pool. Conservation geneticists Dr. David Phillipp and Dr. Julie Claussen explain this phenomenon as such:

“By minimizing mortality and controlling environmental conditions, hatcheries strive to thwart, not mimic, the evolutionary and ecological processes that shape wild fish.”

It’s well-studied that hatchery fish can have negative impacts on wild fish. A recently published synthesis of 206 publications determined that 83% of studies reported adverse effects of hatchery fish on wild fish. Only 3% of studies reported beneficial effects of hatchery fish on wild fish, and such studies were focused on intensive recovery hatcheries that support extremely depleted wild populations. In addition to dilution of the wild salmon gene pool, hatchery fish are often larger at release compared to wild smolts, and can outcompete wild fish for the same resources.

By artificially propping up salmon populations with hatchery fish, we run the risk of ignoring the drivers of salmon declines in the first place, namely habitat loss, overfishing, and climate change.

Hatcheries aren’t accomplishing their goal

In the beginning, the goal of hatcheries was to buoy an ailing fishing industry. Yet, in the years since hatcheries were first introduced, commercial fishing catches have declined precipitously, and many salmon populations are at all-time lows. Governments often need to enact fishing closures to protect endangered wild fish, putting people’s livelihoods at risk and creating uncertainty in communities that base their economies around fishing.

With the mountain of evidence indicating the ills of hatcheries, it’s concerning to realize that the majority of hatcheries are taxpayer funded. We are quite literally paying for an activity that has been degrading wild salmon populations. In the Columbia River Basin (US), a watershed decimated by hydropower, researchers have calculated that it costs taxpayers up to $400 per fish to maintain salmon populations upstream of the dams. That money could be better put to use restoring habitat and removing dams, short-term investments that pay for themselves in the long run.

The nuance of hatcheries

Producing salmon in hatcheries began because of the decline of wild salmon. As such, the primary reason behind building hatcheries was to maintain or increase the amount of fish caught. Over time, the reasons for producing salmon broadened to include assessment of fishery impacts (through tagging), and to expand local engagement in salmon recovery through stewardship and volunteer efforts.

In this way, hatcheries become associated with “salmon recovery.”

Today, we know that hatcheries have generally failed in their objective to recover wild salmon. Worse, in many places hatcheries are contributing to the decline in wild salmon.

Being clear about goals behind hatcheries is paramount. In the case of conservation, rebuilding extremely depleted populations must have the ultimate goal of creating a self-sustaining population that doesn’t need annual hatchery input to persist. Hatchery supplementation must be able to turn off.

Even production hatcheries must not produce more salmon than sustainable fisheries can catch and that spawning grounds can support. Unfortunately, this is seldom the case.

In 2019, production hatcheries in BC and Yukon released 306 million juvenile salmon to support fisheries harvest. At this scale, their impact on wild fish can be significant. Populations that are enhanced for harvest can show trends where hatchery fish become disproportionately abundant over time, effectively turning a wild population into a semi-domesticated population.

The future of hatcheries

We think of hatcheries as a set of crutches. At a small carefully done scale, they can supplement struggling populations to find their footing, but at a larger scale, they hold back populations trying to recover. By shifting to sustainable fishing practices, restoring freshwater habitat, and fighting climate change, we envision a future where wild salmon populations, and the communities and ecosystems they support, are thriving in wild rivers.

Support our mobile lab, Tracker!

Our new mobile lab will enable the Healthy Waters Program to deliver capacity, learning, and training to watershed-based communities. We need your support to convert the vehicle and equip it with lab instrumentation. This will allow us to deliver insight into pollutants of concern in local watersheds, and contribute to solution-oriented practices that protect and restore fish habitat.