Chum salmon discards in the Great Bear Rainforest

Groups call on Minister to “move fisheries into the 21st century”.

North Coast BC commercial salmon fishermen have discarded over 20% (by weight) of their total catch so far this year, including 1.37 million pounds (624 metric tons) of chum salmon. Many of these fish are from stocks that federal fisheries scientists have described as being of “special conservation concern”. Most of the discarded fish are not expected to survive, losing their only chance to spawn after spending four years in the Pacific Ocean. One-half of these chum discards (310 metric tons as of August 11) came from areas in and around the Great Bear Rainforest on Canada’s west coast.

The ecological cost of chum discards

The abundance of many stocks of chum salmon on BC’s central and north coast is too low to withstand significant fishing pressure. There are also growing concerns over the impact that low salmon abundance has on coastal grizzlies, other wildlife that rely on salmon, and the healthy functioning of salmon-dependent ecosystems.

The massive amounts of nutrients and energy that salmon bring back to BC’s watersheds every year can be likened to the wildebeest migrations of the Serengeti. Similar to their African ungulate counterparts, spawning salmon provide an essential seasonal food to many species. For coastal grizzlies, the health of individuals, the number of cubs per female, and population densities are all strongly related to the consumption of salmon. Grizzlies have smaller and less frequent litters in lean times. Given that chum used to provide a high percentage of salmon to these bears, its decline could result in fewer bears and less resilient populations over time.

Bears drive productivity within coastal streams and forests by transferring salmon carcasses from streams to the forest floor, providing nutrients and energy to the entire stream and stream-side foodwebs, including insects, birds, mammals and other fish. In terms of nutrients, 310 metric tons of discarded chum salmon translates to 9 metric tons of nitrogen and 1 metric ton of phosphorous, 80% of which would have been of delivered by bears to the forest.

The economic value of spawning salmon

The rising popularity of wildlife ecotourism is suggesting that salmon may be worth more to coastal economies alive than dead. Wildlife ecotourism has grown impressively in the past 20 years. The number of operations bringing tourists to see BC’s coastal bears has more than quadrupled since the 1990s and local First Nations have been an important component of this growth. This promising new economic activity requires healthy, functioning ecosystems with diverse and abundant salmon populations. Greater salmon numbers means greater numbers of bears, increasing and protecting economic opportunities for eco-tourism bear-viewing and other salmon-reliant activities.

Sustainable salmon fisheries are possible

Changing the way we fish for salmon could significantly reduce impacts to stocks of concern, like chum salmon in the Great Bear Rainforest. This could be achieved by moving fisheries away from “mixed-stock” fishing areas where it is impossible to target strong stocks while avoiding stocks of concern, by employing well-proven selective fishing techniques, and by transitioning to quota-based fisheries (instead of the antiquated competitive fisheries now occurring on BC’s north coast). In many other BC fisheries all boats must have on-board independent observers or video cameras to monitor by-catch and compliance with fishing regulations. The sustainability of BC’s salmon fisheries would benefit from similar measures.

Download the pdf version with the backgrounder Chum discards and backgrounder (PDF)

Read our press release.

You can help

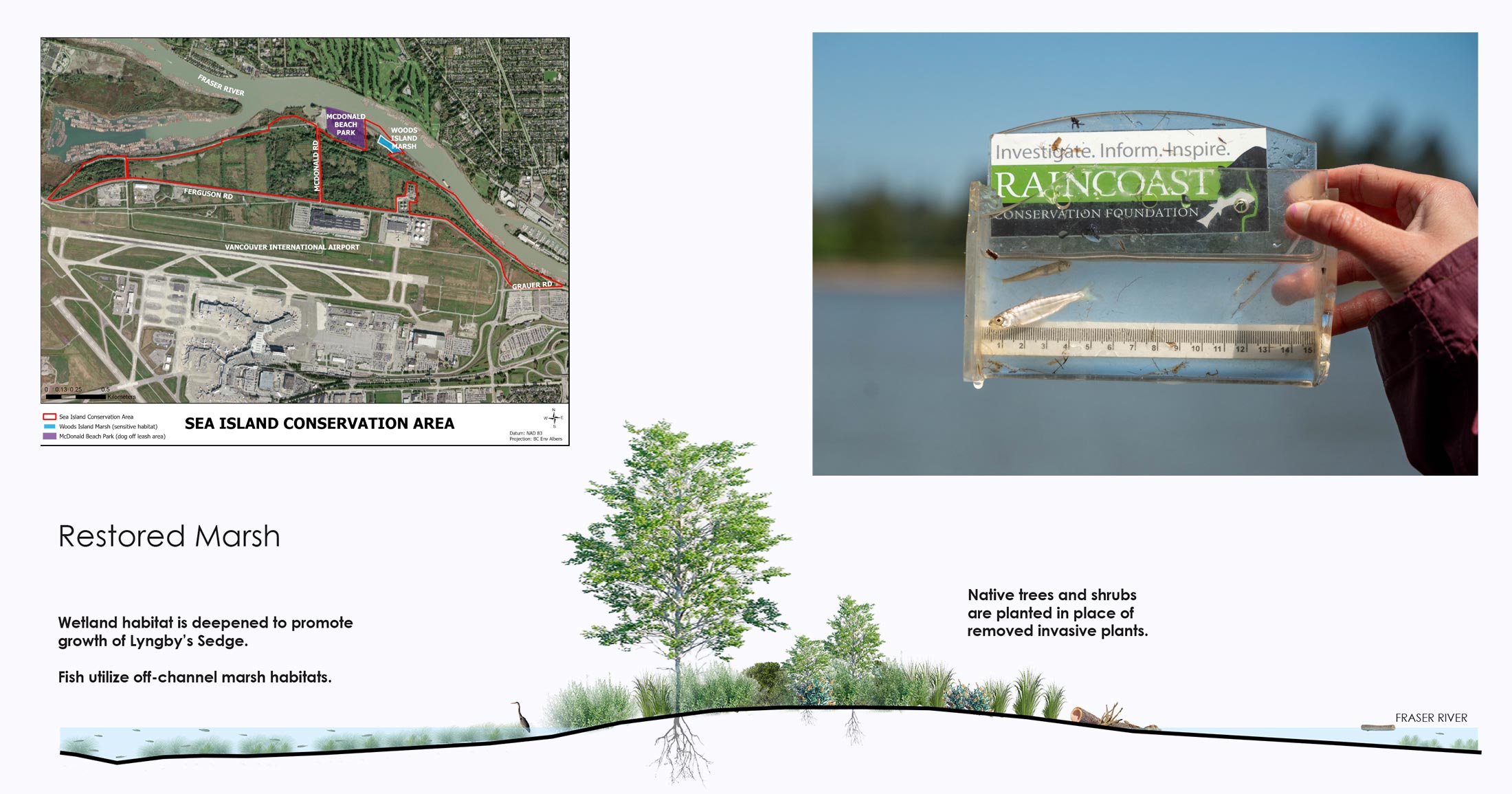

Raincoast’s in-house scientists, collaborating graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and professors make us unique among conservation groups. We work with First Nations, academic institutions, government, and other NGOs to build support and inform decisions that protect aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, and the wildlife that depend on them. We conduct ethically applied, process-oriented, and hypothesis-driven research that has immediate and relevant utility for conservation deliberations and the collective body of scientific knowledge.

We investigate to understand coastal species and processes. We inform by bringing science to decision-makers and communities. We inspire action to protect wildlife and wildlife habitats.