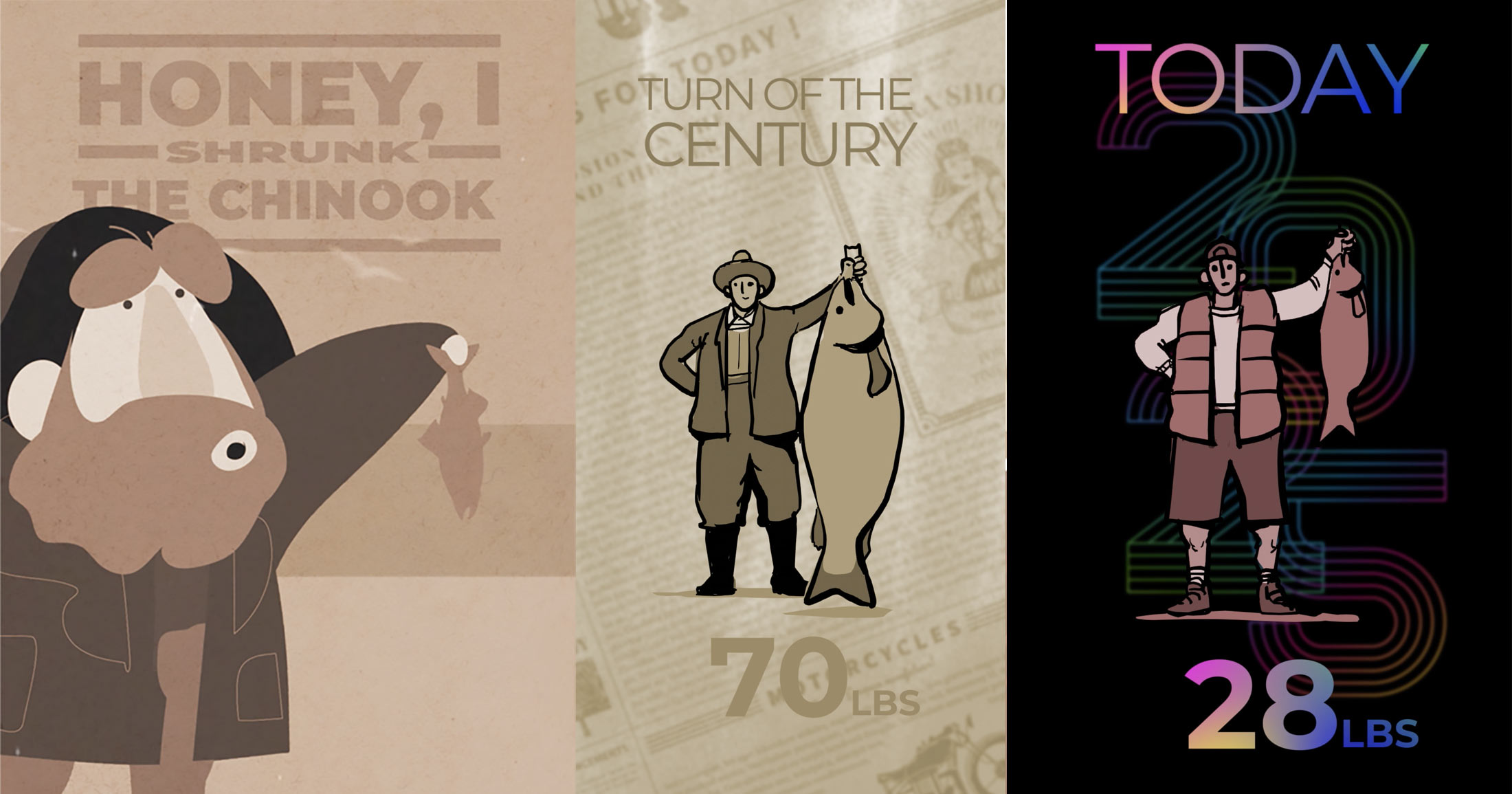

Chinook salmon are getting smaller – and one explanation is uncomfortably familiar

Honey, I shrunk the Chinook.

At the beginning of the 20th century, a mature Chinook truly was the king of salmon, with prized fish exceeding 70 pounds. Today, anglers celebrate landing a 30-pound fish. In just over a century, truly large Chinook have shifted from commonplace to rarity.

This reduction in body size has consequences. Smaller females produce fewer and smaller eggs. Smaller eggs lead to smaller fry, which can have lower survival. Smaller female Chinook may also struggle to use the spawning habitats their ancestors once occupied, because carving deep, scour-resistant redds (nests) in coarse river cobble requires a body size many no longer attain.

So why – and how – is this happening?

One factor is how we fish

Before the 20th century, salmon were largely caught in or near rivers, where most fish had already matured and were returning to spawn. As fishing technology advanced, harvest shifted farther out into the ocean. For Chinook, this didn’t just change where fish were caught – it changed which fish were caught.

Along with adult Chinook headed for their home rivers, marine fisheries also began capturing immature Chinook that were still growing in coastal waters. Some of these fish might otherwise have spent months or even years growing before returning to spawn.

This strategy – growing for extended periods in coastal waters rather than far offshore – is most prominent in Chinook salmon.

In the early 1900s, many Chinook returned to spawn at six or even seven years of age. When fishing moved away from rivers further into coastal marine waters, an unintended consequence was the capture of these younger, still-immature fish that remained closer to home.

When immature fish are consistently removed from a population, the genes associated with growing older and larger decline in frequency. Fish that mature earlier gain a survival advantage. Over generations, this selective pressure drives an evolutionary shift toward younger maturation at smaller sizes.

Today, many Chinook return to spawn at much younger ages and up one-third the body size of their historical counterparts. Six- and seven-year-old Chinook are now almost nonexistent, and five-year-olds are far less common than they once were.

This shift reflects unintentional, human-driven evolutionary pressure, with far-reaching ecological and social consequences. Smaller Chinook mean less food and economic value per fish for people, diminished use of historic large-gravel spawning grounds, and less biomass delivered to wildlife, especially per fish.

So how can we fix this?

A key solution is the re-establishment and expansion of freshwater terminal fisheries. These fisheries operate in or near rivers at the end of a salmon’s migration. Terminal fisheries were used by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years and by early settlers across the Pacific Northwest.

Fishing closer to rivers allows salmon to fully mature in the ocean, helping protect the genes of the largest and oldest fish. It also increases the likelihood that the biggest females can escape harvest and reach their spawning grounds. By shifting fishing pressure from the open ocean back to terminal locations, we can continue fishing while allowing Chinook body size to recover over time.

The benefits would ripple outward – strengthening ecosystems, feeding Chinook-dependent wildlife like endangered killer whales, and supporting the people who live and work in Chinook salmon watersheds.